‘Atmospheres of Knowledge Production’ as a frame for exploring data in the home

Over the past few months, I’ve organised three sessions bringing together researchers from the University of Edinburgh’s Science, Technology and Innovation Studies (STIS) to think through how understandings of space and affect intertwine with the production of knowledge in our different research projects. The researchers have diverse disciplinary backgrounds and research interests: among us are a geographer, three sociologists, two historians, an STS scholar, and two anthropologists. Our research foci extend across a range of topics, including pandemic simulations, the research practices of seabird ornithologists, material culture in medical education, expectation in translational genetics research, care relations in the use of epilepsy-monitoring devices and the places of scientific practice and technology production.

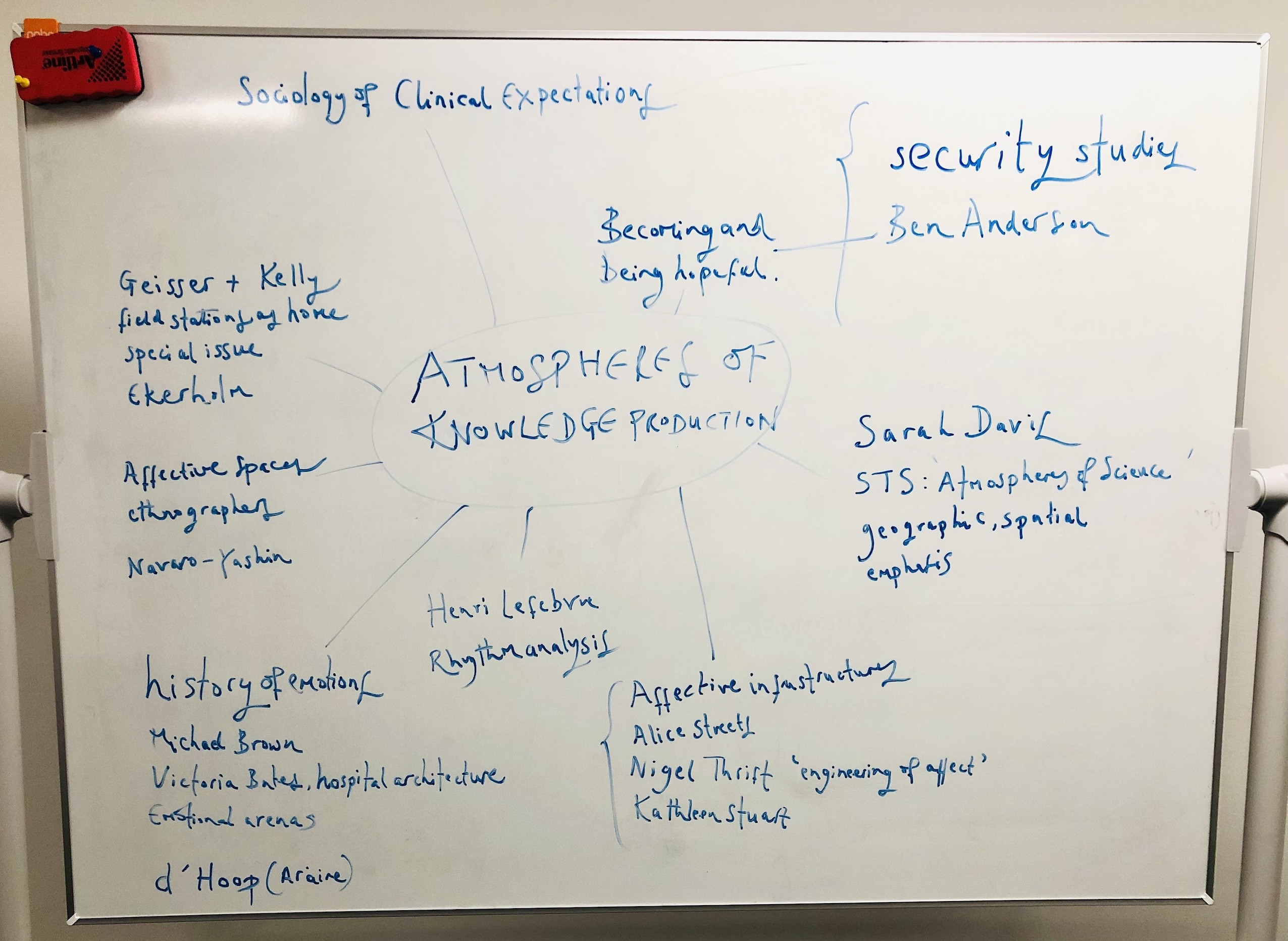

Following a STIS departmental seminar by Dr Jenny Bangham that touched on the different spaces of clinical knowledge production in the history of genetic counselling, we realised that each of us had been thinking about the intersection of space, affect and knowledge production – though we lacked a shared notion to ground these ideas. Drawing on Ben Anderson’s (2009) concept of “affective atmospheres”, we coined the term ‘atmospheres of knowledge production’ to capture this strand of thinking.

Atmospheres, Anderson proposes, are ambiguous patterns of feeling and emotion. They sit at the intersection of and traverse multiple 'opposites’: the present and the past; presence and absence; the individual and the collective; the personal and the impersonal; the determinate and the indeterminate. They emanate from the people, things and spaces of everyday life, arising from the relational areas between these components rather than belonging to one component itself. They become greater than and envelop all things involved; and are irreducible to the components that make them up. Atmospheres can be charged, intense, contagious, turbulent, calm and safe. An atmosphere can pertain to a space (e.g. of a room, a city), a period of time (the morning, the spring, the 50s), or group of people (a couple, a community). Atmospheres can be hard to define, dynamic, and fleeting, as well as definite and intelligible for people who experience them.

We also draw on a tradition that has acknowledged and centred space at the heart of knowledge production, for example in the laboratory (Latour & Woolgar 1986) and the field station (Geissler & Kelly 2016). Science and Technology Studies has increasingly found ‘space’ as an organising principal for empirical work (Henke & Gieryn 2008). Through our discussions, we have considered how we might progress from ‘space’ or ‘place’ to ‘atmosphere’ as a frame through which to approach the things we know and how we come to know them. Some of the questions we’ve been asking include: How might the notion ‘atmospheres of knowledge production’ offer a useful frame through which to understand the worlds explored in our diverse research endeavours? How does it articulate with other, related notions e.g. ‘socio-geographies of knowledge production’ (Massey 2005)? While the first sessions have only begun to probe at these questions, two clear implications for thinking through ‘atmospheres of knowledge production’ have emerged: one methodological, the other empirical.

Methodologically, atmospheres offer a lens through which to reflect on our own production of knowledge as social science researchers and how we as researchers influence the atmospheres we encounter in the process of fieldwork. For example, Kohelmainen (2020) attends to their own embodied response to the atmospheres they encounter during fieldwork as a way to understand the cultures underlying the communities they study. Kohelmainen mapped their own movement into, within, and outside the existing atmospheres, noting the times they were caught up in an atmosphere, when they were pulled out of the atmosphere, and what contributed to the pulling. They remarked on how some atmospheres created a situation where the production of data, through the writing of fieldnotes for example, felt inappropriate. In this way, atmospheres in the field can shape the ways in which social science data is produced.

Empirically, we can explore the ways in which atmospheres in the field contribute to and shape the production of knowledge in the specific communities of practice we study. Geissler and Kelly’s (2016) tropical and arctic scientific fieldsites are simultaneously separate from the local communities around them and yet are porous, intimately influenced by the places in which they are situated. These fieldsites open up unique opportunities to explore the aesthetic and affective dimensions of scientific research as the knowledges produced there are influenced by local histories, politics, and culture in ways that are distinct from laboratory science.

Both approaches to atmospheres have already become relevant for my work on the DARE project, where my fieldwork concerns the relationship between data, learning and care in the home. My work as part of the ‘Home’ work package traces the production of data in home-based clinical trials. I ask, what happens as the home is made into a site for clinical research -- what happens to the production of clinical knowledge, to the processes of research itself, to the home? How do everyday practices in the home become intertwined with the production of data used for clinical trials and what does this mean for the ways in which patients and families relate to disease, the health system and each other?

To approach an answer to some of these questions, I have been conducting ethnographic fieldwork with a global technology company that develops applications and algorithms for producing and analysing data in home-based trials. As part of this work, I’ve attended weekly and fortnightly meetings of those who work closely with patient organisations and patients themselves to develop apps for producing data in the home, as well as meetings with data scientists who process and analyse this data. I’m also conducting interviews with those involved in the process of data production and analysis, including research participants and their families. I have accessed ‘the home’ in different ways, through discussions amongst data scientists around standardising data production in the home, to discussions with patient organisations about how the production of data might fit in alongside patients’ daily routines, to being physically present with families in their homes as they produce data for clinical trials.

The notion of ‘atmospheres’ offers a route into considering my positionality as a researcher within the particular assemblages of people, things, and spaces that make up the forms of home I include in this work. It has allowed me to reflect on the ways my relations with the people inhabiting these spaces influence the data I generate and what we ultimately come to understand about the role of data in the home. To conduct this work, I not only need to create my own site of research within different home spaces, but I also need to form relationships with the people who inhabit those spaces (Street 2016). I depend on the families who take part in clinical trials to welcome me into their homes and on the data scientists and patient advocates to share (through instruction and explanation) the ways they see into, analyse, and organise the home as a site of data production. The production of knowledge in the DARE project hinges on the hospitality of these families and the global tech company, on the delicate navigation of relationships, and the willingness to share the intimate space of the home and the work place with a researcher.

So far, I’ve been welcomed into the home of three families participating in clinical trials for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). This severe genetic disorder affects the muscular development of children, almost exclusively boys. This disorder is progressive and has no cure; many people with this disorder don’t live past early adulthood. Participating in clinical trials is often the only way in which families can access new therapies for their children. From meeting several families navigating this disorder and attending a conference organised by the largest charity for DMD in the UK, Duchenne UK, I have a small idea of the delicate balance these families maintain throughout their daily life. It is one that encompasses both the need to accomplish daily routines like going to school, preparing lunch, managing relationships with siblings and playdates with friends, as well as doing physiotherapy exercises, attending doctors appointments, taking multiple medicines, being aware of activities that used to be accessible, perhaps just last week, but are no longer possible due to muscle deterioration and weakness. The presence of uncertain futures, of love and sadness and mourning for childhoods that will never be ‘normal’, of daily routines and preparedness for an emergency, all encompass this daily life.

When visiting these families, I felt the atmosphere of safety they had created in their homes. This atmosphere arose partially through the ways the families accommodated their sons in the present, and through future preparations for when their mobility declines. The homes I visited had ongoing construction projects: widening doors to allow easy passage of a wheelchair, building a bathroom on the ground floor to avoid multiple trips upstairs, installing a hoist in the bedroom to help with transfers from wheelchair to bed. All of these homes also had designated spaces for the boys’ individual use: an alcove set up with a computer for gaming and shelves displaying models of their favourite cars; a cardboard box spaceship filled with blankets for comfort, into which one boy could retreat during the tantrums that are especially common with the high use of steroids in children with DMD.

As a researcher coming into these homes -- these spaces made safe by acts of practicality, love, and protection -- in the context of participation in clinical trials, I felt I was an unwelcome reminder of the difficult reality these families navigate. Arriving at one home in particular, I was told as soon as I arrived that I could keep my shoes on. I wasn’t offered anything to drink, no water or tea. I was led swiftly to the room where I’d be observing their data collection. I decided not to stay long, sensing from the atmosphere that I’d intruded into a space that was being kept safe. In total, the visit lasted around 20 minutes, inclusive of observation and an interview. This atmosphere contributed both to my ability to conduct research – my methodology -- as well as my understanding of the realities of the families navigating this disease – my empirical material. On the one hand, it limited my time spent in the home and my observation of the relations between family members. Empirically, however, this atmosphere provided insight into the type of safety cultivated in the home – to the preciousness of the home, to the delicate situation of the disease, to the protection parents felt toward their children. This atmosphere, in itself, provided insight into the daily lives, values, and emotions of the family; to the realities of this disease and what participation in clinical trials may mean for a family – a complicated balance between wanting access to therapies and maintaining a ‘normal’ daily life without following protocols of data collection or introducing researchers to the home. Through this fieldwork encounter, while I felt my view of this particular home life was inhibited by the atmosphere, this same atmosphere provided deep understanding into the ways in which this family lives, the complexity of participating in clinical trials and incorporating the production of data into everyday life.

‘Atmospheres’ in this way has opened up ways to attend to and reflect on the methodology of this work as well as the empirical material that will come to inform my understanding of data, care, and learning in the home. Moving forward, I’ll be thinking about questions such as: Who and what contribute to the atmospheres I encounter? How do atmospheres shape the production of knowledge and in turn, how does the production of knowledge shape atmospheres? How does data collection in the home, for example, shape the atmosphere of the home? How does our own data collection influence the atmospheres of the spaces we study? I’m also interested in other questions, such as, how are atmospheres influenced by dynamics of power? Who has the agency to shape an atmosphere, and who doesn’t? Ultimately, I hope these meditations on and applications of atmosphere help to extend our understanding of what a home can be and what a home might become in the context of data-driven healthcare.

Our working group plans to continue drawing together our disciplinary backgrounds and tracing common themes across our diverse research interests through continued, future discussion.

References

Anderson, B. (2009). Affective atmospheres. Emotion, space and society, 2(2), 77-81.

Geissler, P. W., & Kelly, A. H. (2016). A home for science: the life and times of tropical and polar field stations. Social Studies of Science, 46(6), 797-808.

Henke, C. R., & Gieryn, T. F. (2008). 15 Sites of Scientific Practice: The Enduring Importance of Place. The handbook of science and technology studies, 353.

Kolehmainen, M. (2019). Affective assemblages: Atmospheres and therapeutic knowledge production in/through the researcher-body. In Assembling therapeutics (pp. 43-57). Routledge.

Latour, B., & Woolgar, S. (1986). Laboratory life: The construction of scientific facts.

Massey, D. B. (2005). For space.

Street, A. (2016). The hospital and the hospital: Infrastructure, human tissue, labour and the scientific production of relational value. Social Studies of Science, 46(6), 938-960.